Leaving Oracle successfully is rarely about choosing the perfect target database. By the time organizations reach this stage, they have usually already selected AlloyDB, Cloud SQL for PostgreSQL, or another managed engine. What differentiates success from failure is not the destination, but how teams organize the work, sequence decisions, and accept that the database is no longer the center of gravity it once was.

This third part builds on the previous two articles. In Part 1, we discussed why migrating away from Oracle is fundamentally a strategic and architectural decision. In Part 2, we examined what actually breaks when Oracle-specific behavior disappears. This article focuses on the patterns that consistently work in real migrations — and the ones that do not.

Successful Migrations Start with Ownership, Not Tools

Teams that succeed make one decision early and explicitly: the application owns the behavior, not the database. This sounds obvious, but it runs directly counter to decades of Oracle-centric design, where business logic, scheduling, workflows, and even error handling lived inside PL/SQL.

In successful migrations, database teams do not attempt to recreate Oracle inside PostgreSQL. Instead, they work with application engineers to identify which behaviors must be preserved, which can be simplified, and which should move into application code or platform services. Database Migration Assessment and Database Migration Service help reveal what exists, but they do not decide what should survive.

This shift in ownership often requires uncomfortable conversations. Teams must accept that some refactoring is not optional. Attempting to preserve every stored procedure and package usually results in fragile systems that technically work but are difficult to maintain and evolve.

The Most Effective Migrations Are Phased, Not Atomic

One of the strongest predictors of success is whether the migration is approached as a series of controlled steps rather than a single cutover event. Teams that attempt to migrate schema, data, and logic all at once tend to accumulate risk rapidly.

Successful teams typically begin with schema and data movement, using tools like DMS to establish continuous replication. This creates a stable foundation and allows teams to validate data correctness early. Only after data flows reliably do they tackle procedural logic, triggers, and batch workloads.

Crucially, these teams run the new system in parallel with Oracle for a meaningful period of time. This is not just about validating row counts. It is about observing behavior under real workloads and identifying subtle differences that assessments and test suites often miss.

Translation Is a Starting Point, Not the Finish Line

Where AI-assisted translation is used — for example, converting PL/SQL to PL/pgSQL — successful teams treat the output as scaffolding. The goal is not to achieve a one-to-one translation, but to accelerate understanding.

Translated code is reviewed, simplified, and often partially discarded. Packages are flattened. Autonomous transactions are redesigned. Schedulers are replaced with managed services. Over time, the database becomes simpler, not more complex.

Teams that skip this cleanup phase often find themselves locked into a hybrid design that preserves Oracle-era complexity without Oracle’s guarantees.

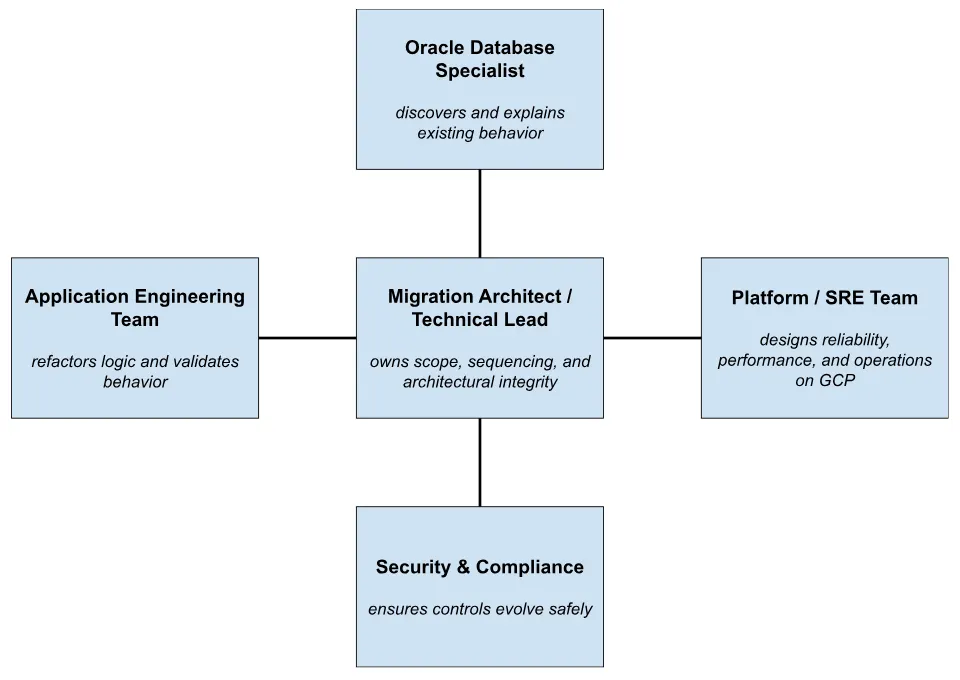

The Migration Team: Who You Actually Need and Why

Successful Oracle migrations are rarely driven by a single role or team. They require a deliberately assembled group of professionals, each owning a different risk dimension of the migration. When any of these roles is missing or underpowered, problems tend to surface late, when fixes are expensive.

At the center is usually a technical migration lead or architect. This person owns the end-to-end shape of the migration: target architecture, sequencing, trade-offs, and non-goals. They are not simply a database expert; they must understand application behavior, cloud primitives, and organizational constraints well enough to say “no” when a migration approach is heading toward Oracle reimplementation.

Alongside them is a database specialist with deep Oracle experience. This role is critical early on. Their job is not to defend Oracle, but to explain it — to identify which PL/SQL packages matter, which schemas hide business logic, and which features are truly in use versus historical residue. They are often the fastest way to distinguish real risk from noise uncovered by assessment tools.

Equally important are application engineers who own the consuming systems. In successful migrations, these engineers take responsibility for logic that must move out of the database. They refactor workflows, error handling, and transaction boundaries, and they validate that application behavior remains correct as the backend evolves. When application teams are not deeply involved, migrations stall at the first behavioral discrepancy.

A platform or SRE role is also essential. This team designs connectivity, observability, backup and recovery, performance testing, and failover strategies for the new database engine. Oracle often hid operational complexity behind expensive defaults. On Google Cloud, these concerns are explicit and must be designed intentionally.

Finally, strong migrations include security and compliance stakeholders early, not as a final gate. Authentication models, encryption, auditing, and access controls often change significantly when leaving Oracle. Addressing these late can force architectural compromises that undo earlier gains.

What matters most is not the size of the team, but clarity of ownership. Each role must know which failures they are accountable for preventing.

Anti-Pattern: The DBA-Only Migration Team

One of the most common — and costly — mistakes is staffing an Oracle exit as a DBA-only initiative. In this model, database administrators are expected to assess schemas, translate PL/SQL, migrate data, validate behavior, and somehow guarantee application correctness. This fails not because DBAs lack skill, but because the problem is not purely a database problem. Application logic embedded in Oracle cannot be safely refactored by people who do not own the application, and operational concerns cannot be solved without platform expertise. DBA-only migrations often appear successful until late-stage testing reveals subtle behavioral regressions that no one feels empowered to fix.

Team Diagram Concept

Executive Takeaway

If you staff this migration like a database upgrade, expect application regressions and late surprises.

If you staff it like a modernization program with shared ownership, expect slower early progress — and dramatically lower risk at cutover.

Cost-of-delay warning: every month spent with the wrong team structure compounds rework later, because architectural decisions harden before the right people are empowered to change them.

Who Should Own the Budget?

Successful organizations place budget ownership with a product, platform, or modernization sponsor — not exclusively with the database or infrastructure team. This signals that the goal is system correctness and long-term velocity, not merely license reduction. When the budget sits solely with a DBA or infrastructure function, incentives skew toward minimizing short-term effort rather than funding the application refactoring and platform work that actually reduce risk. Executive ownership aligned to application outcomes consistently leads to better sequencing, clearer trade-offs, and fewer surprises at cutover.

Organizational Alignment Matters More Than Engine Choice

A recurring theme across successful migrations is cross-functional alignment. Database engineers, application developers, SREs, and security teams must all be involved early. Oracle migrations fail most often when they are treated as a database team’s responsibility alone.

In organizations that succeed, leadership explicitly frames the migration as modernization, not cost-cutting alone. This framing legitimizes refactoring work and reduces pressure to rush toward a superficial completion date.

Executives also play a role by accepting that value is delivered incrementally. The first milestone is not “Oracle turned off,” but “critical workloads behaving correctly on the new platform.”

The End State Looks Boring — and That’s a Good Thing

Ironically, the most successful Oracle migrations end with a database that feels almost boring. There are fewer stored procedures, fewer triggers, and fewer hidden behaviors. The database stores data, enforces constraints, and supports queries efficiently.

Complexity does not disappear; it moves to places where it is more visible, testable, and versioned. This is the real payoff of leaving Oracle. Not lower licensing costs, but a system that teams can reason about and evolve without fear.

Final Thoughts

Migrating away from Oracle is not about replacing one database with another. It is about changing where decisions live and how systems are designed. Teams that succeed accept this early, move deliberately, and resist the temptation to recreate Oracle in a different engine.

If Part 1 explained why leaving Oracle is unavoidable for many organizations, and Part 2 showed what breaks when it is done carelessly, this third part shows that success is possible — but only when migration is treated as engineering work, not a mechanical exercise.